State Bauhaus in Weimar and the Haus am Horn (Part 1)

In 2019, the 100-year anniversary of Bauhaus was celebrated in a big way. This event attracted international interest and gave occasion to take a closer look at the “Haus am Horn”, the Bauhaus model home built in Weimar in 1923, from the perspective of the clay brick and tile industry. Please read the first part here.

Introduction

“State Bauhaus” was the name the architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969) gave to an innovative art school that he founded in Weimar on 1 April 1919. “The ultimate goal of all art is the building! The ornamentation of the building was once the main purpose of the visual arts, and they were considered indispensable parts of the great building,” wrote Gropius in the Bauhaus founding manifesto. In 1925 the school was moved to Dessau, then in 1932 to Berlin, before it was closed on 19 July 1933 under the pressure of the National Socialists. Despite its short existence lasting just 14 years, the art school had a major impact on the design and architecture of the 20th century. It is associated primarily with austere architecture reduced in form and colour, simple and elegant functionality as well as clear-cut and seemingly timeless modern design.

The “Haus am Horn” in Weimar

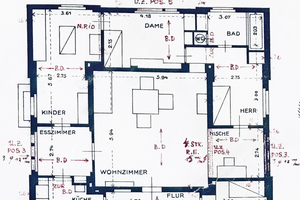

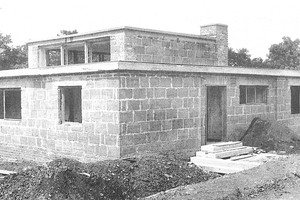

The reason for the construction of this model house, a sort of atrium house for a family of three or four according to a design by Georg Muche, was the first Bauhaus exhibition from 15 August to 30 September 1923.

The house was intended to offer a possible answer to the shortage of housing at that time. The basic considerations behind it were the application of modular, low-cost construction, a use-oriented layout and living comfort thanks to modern technology. The model house is the only complete testimony of State Bauhaus in Weimar. In 1996, as part of Bauhaus and its significant places of work, it was declared a world heritage site by UNESCO.

Responsible building owner was Walter Gropius himself, the construction work was undertaken by Soziale Bauhütte Weimar. After requests to US American industrialists and the city of Weimar had remained unsuccessful, the building project was ultimately financed by the industrialist Adolf Sommerfeld. For him, Gropius had designed the Sommerfeld house in Berlin-Lichterfelde in 1920/21. Many of the contracted companies worked at cost, but used their materials to good advertising effect.

The Haus am Horn was definitely intended as a building plan, the alternately used descriptions “model house”, “type house” or “test house” leave no doubt about this. In response to a first publication about the model house in Velhagen & Klasings monthly magazine from the year 1923, a total of 39 interested enquiries “for the same or similar projects” were received. For example, in reply to an enquiry from J. Platzer in Vienna, it was agreed that he could obtain the plans, building description and other necessary documentation for the test house for a fee calculated according to the terms of the scale of fees for architects and engineers.

No one knows how many of the building plan sets were sold and how many houses were actually built according to these. In any case, the famous Haus am Horn has an unequal twin sister in the small town of Burbach in Siegerland: the Ilse Country House. It was commissioned by the engineer Willi Grobleben, Technical Director of Westerwald-Brüche AG (WAG) in summer 1924. The country house named after the owner’s daughter served initially as a guesthouse for the company, but was used several years later as a home for the Grobleben family. Unfortunately, it is not known who the architect of the house was, but it is assumed that he must have known the Haus am Horn or at least been familiar with the plans for it as the two houses in Weimar and Burbach are similar in their layout. It is not known whether documentation or plans for the Haus am Horn were bought from State Bauhaus for the construction of the Ilse Country House. It is, however, also possible that Grobleben travelled the 290 km to Weimar in 1923 and personally took a look at the Haus am Horn.

The now also listed Ilse Country House has been owned by the town of Burbach since 2017 and – just like the Haus am Horn in Weimar – is again open to the public.

Building construction and building materials

The building period needed for the detached Haus am Horn was four months (April to August 1923), but fell in the time when Germany was struggling with economic inflation. For this reason, the choice of building materials and the construction methods was not unlimited. That the house could nevertheless be built in line with state-of-the-art construction ideas was mainly thanks to the understanding and cooperation of those industries involved.

In the choice of building materials and the building construction, those that played to a new synthetic building concept were preferred. Substitute construction concepts were deliberately eliminated, instead importance was attached to conformity of material and construction to show a possible way forward beyond the economic restraints at that time.

In the following, the wall and floor construction and the construction products used are more closely considered and compared with brick construction today. One focus is thermal insulation of the exterior wall as then work was always done in comparison with brick masonry.

Exterior walls

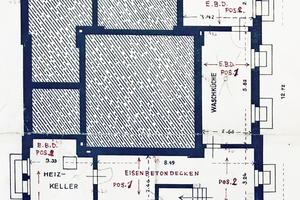

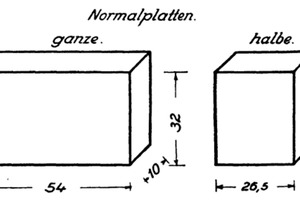

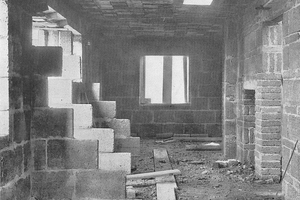

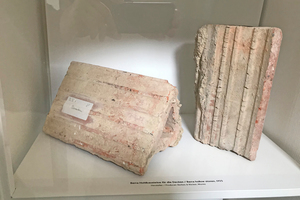

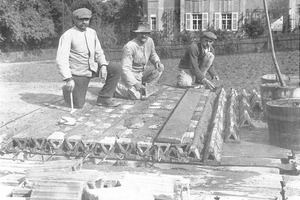

For the wall and floor structure, prefabricated lightweight blocks of cement-bonded clinker concrete (mixing ratio 1:12), known also as Jurko slabs (abbreviation for J. and R. Koppe), were used.

The brothers Johannes and Robert Koppe, both having completed an apprenticeship as bricklayers, ran together a “studio for the applied arts” in Leipzig and at the end of the 1910s developed this type of masonry brick and associated construction concept.

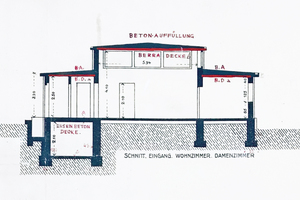

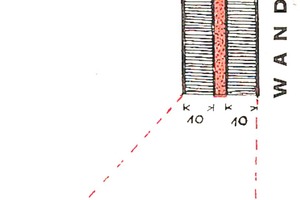

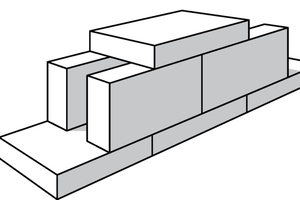

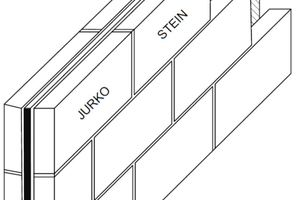

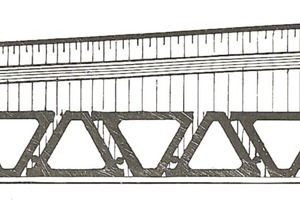

This consisted of two wall leaves of alternately vertically and horizontally laid clinker concrete blocks joined to a wall with enclosed air spaces. With a 32-cm-thick cavity wall, the inventors calculated a cost saving of 50 to 60 percent (less coal, transport and mortar) and a weight saving of 70 percent compared with a 38-cm-thick solid brick wall. In 1916, this system was presented at the ”Economical Building Materials” exhibition in Berlin.

These double-leaf exterior walls at Haus am Horn constitute a further development of the “economical construction” proposed by the Koppe brothers in Leipzig consisting of alternately horizontal and upright slabs. To insert a continuous layer of Torfoleum, compressed peat, as insulation, the necessary binder layers between the Jurko boards were replaced with galvanized wire wall ties in each joint. A binder layer was only included under the support for floor of the ground floor.

The double wall slabs with the Torfoleum insulating boards brought significant savings compared to a brick wall built with standard-format bricks (old “Reich” format l/b/h = 250/120/65 mm) in respect of material, transport and wage costs, built area and heating requirement.

Besides the Haus am Horn and the Dessau Masters‘ Houses, Jurko slabs were used in exterior wall construction in many iconic buildings of classical modernism.

The Jurko slabs for the model house were produced by the company Verband sozialer Baubetriebe GmbH Berlin at its Nordhausen plant.

Frick/Knöll: “The slabs are very easy to handle and can be easily trimmed. Building with them is therefore fast and cheap. The slabs can be nailed and are first class in terms of heat insulation; plaster sticks very well to them. In terms of structural stability, the masonry is suitable for private residences.“

As advantages compared brick masonry of standard format bricks, the following savings were emphasized:

of coal, because not fired

of mortar, because few joints are required

of transport costs, because of the low tare weight

of built area, because of the low wall thickness

of working wages, because of the large format of the slabs

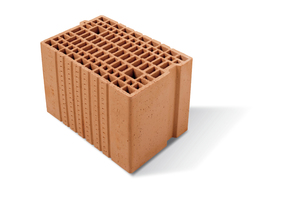

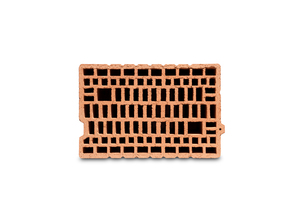

These advantages of the Jurko slab wall structure have been eliminated or reversed today. Particularly with regard to the mortar requirement (surface-ground bed joints and tongue-and-groove butt joints) and the wage costs (large-size vertical perforated bricks), modern high-precision bricks score points compared to the concrete blocks. With the use of vertically perforated clay blocks with integrated thermal insulation, the advantage of the low wall thickness is also reversed. And while it is correct that the concrete blocks do not have to be fired, energy is also needed for cement production.

Cement

Cement was used as constituent and joining agent for most building carcasses, from the foundation base to the chimney cover, as a constituent of the “Jurko blocks”, masonry mortar, cast block works, render and plaster from Terranova and asbestos slate slabs (window sills).

The cement was supplied by Deutsche Zementbund GmbH through the Saxon-Thuringian Portland cement factory Prüssing & Co KG auf Aktien in Göschwitz an der Saale (part of Jena since 1969).

Insulation

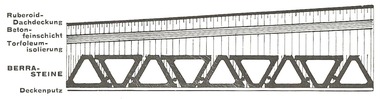

For the thermal insulation of the floors, walls and ceilings, Torfoleum lightweight boards were used.

In 1914, Dr Eduard Dyckerhoff, a grandson of the founder of the Dyckerhoff-Portland-Zementwerke, in Poggenhagen, Province of Hanover, established the company “Torfoleum GmbH”. The use of peat as a raw material for new products was tested, and for the first time peat boards were produced as thermal insulation for construction purposes. They were supplied in thicknesses of 3 to 20 cm. Thicknesses greater than 5 cm were obtained from several thinner boards being stuck together over their entire surface with binder in a machine process. The density reached 160 to 200 kg/m³. The thermal conductivity at 0 °C and an apparent density of 162.5 kg/m³ was measured at 0.0335 kcal/mh °C. With consideration of variations in the apparent density and the test results, a thermal conductivity of 0.040 kcal/mh °C (0.047 W/mK) was declared.

The Torfoleum lightweight boards consist primarily of pressed peat, but do not contain any substances that can decay. To make them more resistant to fracture, coconut fibres were added. The material contains a core impregnation for protection against water absorption. The boards are also reliably impregnated against inflammation.

The Torfoleum boards for the model house were supplied by Torfoleum-Werke Eduard Dyckerhoff, Poppenhagen 50 at Neustadt am Rübenberge. The board sizes measured l / b = 0.50 / 1.0 m with thicknesses ranging from 2 to 5 cm.

Like all organic insulation materials, however, peat reacts relatively sensitively to moisture. During the renovation of houses from the 1920s, workers have repeatedly come across Torfoleum boards that have decomposed under the influence of moisture. For the Bauhaus building in Dessau, Torfoleum was used as insulating material and sometimes proved problematic. It had to be removed from above the auditorium as it dripped into the hall. During the 2017-19 refurbishment of the Kandinsky-Klee Master’s House (built 1925/26), soaked-through Torfoleum was found, which for structural reasons could not be left on the roof.