Life cycle assessment considerations on the recycling of brick and masonry rubble

Summary

Life cycle assessment is a scientific, internationally acknowledged methodology that is conducted according to clearly defined standards and applied in a wide range of sectors – from research to industry. It is a tool used in the analysis, evaluation and optimization of industry processes and in the development of new products. The goals pursued with this methodology are the conservation of resources, closed-cycle thinking, environmental protection, assessment of environmental impact and reduction of climate-damaging emissions.

This methodology, also referred to life cycle analysis, has been applied to mineral construction and demolition waste, which accounts for around a third of the waste produced in Germany and Europe. The objective is to recycle this waste, despite its wide heterogeneity, and channel it as a secondary waste-derived resource into another life cycle.

Analysed in this research was the processing of brick and masonry rubble with a view to using a defined percentage of the material as recyclate in the cement and concrete industry and to increase the recycling rate. The focus here is on use of the material as recyclate and not as vegetation and tree substrate. After an overview of the material and energy flows, there follows the presentation of the investigation framework and a comparison of the environmental impact of different scenarios. The findings reveal potential for ecological optimization in material and process planning.

1. Introduction and motivation

In 2022, 207.9 mill. tonnes of mineral construction and demolition waste were produced in Germany, of which around 10 mill. tonnes consisted of brick and masonry rubble [1]. The recycling rate for construction rubble reached 81.7 % (45.1 mill. t) [1]. The recycling of construction materials and especially the use of secondary resources is an important pillar for a resource-saving, sustainable construction industry.

European and national developments are pointing increasingly in the direction of the circular economy based on Germany’s National Circular Economy Strategy [2], the German Resource Efficiency Programme of the Federal German Government – ProgRess III [3] and, with integration of climate protection, the new Construction Products Regulation (CPR) [4], to minimize especially adverse environmental impacts. From 08.01.2026, with the new CPR, the stepwise disclosure of all core indicators for environmental impacts in accordance with DIN EN 15804+A2 [7] is planned.

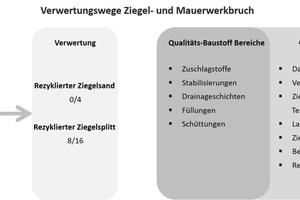

Life cycle assessments make a supporting contribution in the development of new products with the use of recyclates based on life cycle assessment comparisons of construction materials or components as well as in the improvement or optimization of products and processes, e.g. based on the identification of optimization points, so-called hotspots. Primary objective is to use a certain percentage of mineral construction waste like brick and masonry rubble more intensively in recycling rather than for applications such as backfilling material or in the construction of roads and pathways. »Fig. 1 provides an overview of recycling options for brick and masonry rubble.

Crucial for the use of RC material are primarily the purity and quality of the material. For this reason, it is important that any mortar and render or other impurities that may be sticking to the materials are removed at a preliminary stage. High heterogeneity, as is the case for brick and masonry rubble, poses relatively big challenges for the RC process [8]. For this reason, sensor-assisted, optical sorting processes have gained considerable importance in past years. Classical mechanical separation processes – for instance based on physical properties like density – reach their limits here, as these cannot separate the materials in these mixes from each other to an acceptable standard. Optical sorting technology utilizes contactless sensor and imaging systems, for example colour cameras and hyperspectral sensors, combined with intelligent algorithms. With these systems, different types of bricks and impurities can be accurately identified and removed. In research projects, like, for example, [11] – [14], demonstrators have already been developed that sort brick and masonry rubble in the particle size range from 2 – 16 mm with the help of machine learning and imaging processes.

In the present analysis, the focus is on the recycling and utilization of brick and masonry rubble as a secondary waste-derived resource in cement and concrete production. The brick fines or brick sand can be supplied to cement production as a secondary resource. As a result, the necessary content of cement clinker is reduced and a composite cement is produced. High-fired brick and concrete rubble can be supplied to concrete production as a secondary resource, thereby substituting the primary resources of sand and gravel from gravel plants. Brick fines can also be used as aggregate in concrete production as, thanks to the still low pozzolanic reactivity of the material, the required amount of cement per cubic metre can be reduced.

In the production of cement and concrete, a high percentage of greenhouse gas emissions is generated. Around 50 % of the greenhouse gas emissions are formed during the deacidification of the clinker during the firing process in the blast furnace. The remaining share of emissions comes from heat generation for the firing process in the blast furnace as well as from power consumption for processes like grinding, conveying and transport of the raw materials [9]. At the same time, large quantities of cement – 32.9 mill. tonnes (2022) – are produced, with three main types of cement being sold: Portland cement (CEM I with around 24 %), Portland composite cement (CEM II, approx. 53 %) and blast furnace cement (CEM III, approx. 22 %). The objective is a market shift to clinker-efficient cements such as CEM II-C/M, to lower the average content of cement clinker in the cement from 70 % currently to around 53 % (2045) [10]. The major part of the primary raw material required is produced by the German cement industry on the domestic market.

2. Life cycle analyses

To evaluate the environmental impacts, the scientific methodology of Life Cycle Assessment, abbreviated to LCA, is applied. This is described in the standards DIN EN ISO 14040 [5] and 14044 [6]. It is used to analyse the environmental impact of products and services over their entire life cycle. Life cycle assessment considerations can reveal optimization potential in the production process, the composition of the products or in the recycling potential for production-related waste streams. Here, the four phases of a lifecycle assessment are run through in an iterative process:

1. Goal and scope definition,

2. Life cycle inventory (LCI) analysis,

3. Life cycle impact assessment and

4. Assessment and interpretation of the results.

The following chapters 3 to 6 present and discuss the four phases for the optimised processing of masonry rubble.

3. Process chain overview: Brick-rich masonry rubble – recycling and application options

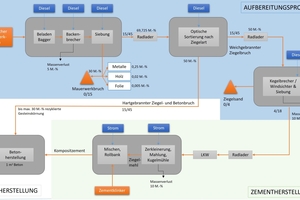

The goal is to use a certain percentage of brick-containing material not only for roof and tree substrate but recycle this to a secondary resource for use in the cement or concrete industry. Starting point for the analyses in the project is a real existing construction material recycling plant that processes brick and masonry rubble. It serves as a basis for the presented material and energy cycles (»Fig. 2). The recycling process chain was complemented with two other follow-on processes. On the one hand, the redirection of the soft-fired brick content (rraw =1.3 – 1.7 g/cm³) into the cement industry, in which a composite cement can be produced by means of grinding and mixing. On the other hand, the production of R-concrete with use of the removed hard-fired brick and concrete rubble (rraw = 1.7 – 2.3 g/cm³).

In the recycling of brick and masonry rubble, various process steps are completed:

1. The rubble is fed to the crushing and screening plant (jaw crusher), in which the material is crushed and screened at 15 mm. A percentage of the 0/15 mm fraction of around 30 mass% is produced, which is used, for example, as roof greening and tree ring material. In this process step metals (0.25 mass%), wood (0.02 mass%) and plastic and lightweight products (0.005 mass%) are removed. The mass losses in the jaw crusher are assumptions based on empirical values from a recycling operation.

2. The wheel loader transports the finely ground material to the optical sorting plant, in which 50 mass% hard-fired brick and concrete rubble are removed. The other part (50 mass%) consists of soft-fired crushed brick and is transported on a wheel loader to the cone crusher.

3. The soft-fired crushed brick is further processed and sized in a cone crusher with integrated air classifier. Here the material is crushed to a size of 4 – 18 mm. Produced are low-gravity materials (wood, plastics, or similar), brick sand and brick rubble, which are further processed. The mass loss in the cone crusher amounts to around 10 mass%.

At this point, the recycling process in the construction recycling plant ends (see the blue-shaded area in »Fig. 2). The secondary resource produced under point 3 is the starting material for other downstream processes. Here the cement industry was chosen and the material and energy streams necessary for this were analysed and modelled (see green-shaded area in »Fig. 2).

4. A wheel loader and lorry transfer the crushed brick to cement production.

5. In the next process step, the crushed brick is ground in a ball mill (mass loss 10 mass%). The basis here is provided by process data from earlier works at the MFPA. In a further process step, the brick fines is mixed with cement-clinker-based cement on a roller bench. The composite cement formed is used in concrete production.

6. In the model, the percentage of crushed high-fired brick and concrete rubble is used as recycled aggregate for concrete production. This results in a saving of the primary resource gravel and sand.

7. In regard to the logistics, no in-plant transports (e.g. wheel loader) are considered, but exclusively transport processes by lorry, which, for instance, transports the brick rubble between brick recycling plant and the cement plant.

4. Goal and scope of the life cycle assessment

In the first phase of a LCA, in accordance with DIN EN ISO 14044 [6], the goal and scope of the assessment are defined (»Table 1). The goal is to conduct an ecological assessment of the alternatives for the integration of brick material from the recycling process in different scenarios. The individual scenarios are shown in »Table 2.

In life cycle assessment, the decision has been made that waste products should be utilized without consideration of the upstream chain. The recycled brick aggregate is included in the calculation unencumbered, i.e. without environmental impacts and the associated emissions. That means that no data on the production of the bricks, on construction, possible refurbishments during the use phase and demolition are channelled into the assessment. Furthermore, the storage of materials and goods is not taken into account. These are not included in the environmental impacts. The process of packaging is not included either. This assessment is derived from the cut-off approach and the end-of-life approach, which says that the responsibility for environmental impacts for the life phases production, erection, usage, disposal (including demolition and transport) ends at the interface between the old and new life cycle [6].

In the scenario, the functional unit of 1 m3 concrete (produced and transport-ready from the factory gate) applies. As the variants differ in the composition in the scenario, »Table 2 provides an overview.

The following were separately assessed as impact categories: greenhouse gas emissions, acidification, eutrophication of salt- and freshwater, ecotoxicity relative to freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems, particulate formation, photochemical oxidant formation, ionizing radiation, land usage divided into agriculture and urban use as well as natural land transformation, depletion of abiotic resources in respect of water shortage, metal shortage as well as the depletion of fossil resources. In addition, the total energy required was analysed.

To achieve a consistency of the data and a comparability of the results, the Ecoinvent database, version 3.8, is used. This concerns datasets for the sectors energy, transport as well as auxiliary and process materials. The datasets were collated with integration of the data from a recycling company. For data not contained in the database, sources from research and science as well as empirical values from project partners and the MFPA were used as a basis.

5. Results of the life cycle assessment considerations for various recycling options for the brick-containing masonry rubble

The results of the environmental impacts are shown in »Table 3. Scenario (1) (column 1) presents the reference scenario and the percentage deviations of the scenarios (2) and (6) differentiated in »Table 2 in comparison with the reference scenario are given (column 2 to 6). The abbreviation A in »Table 3 stands for Aggregate.

Scenario (1) shows the environmental impacts for the use of 100 % cement clinker and without the addition of waste-derived secondary resources as a substitute. The scenarios (2) to (6) are based on different compositions of the composite material for cement production, like limestone and brick fines for composite cement production. The different compositions of the composite material with the addition of brick fines as a secondary resource are based on laboratory tests at the MFPA. In addition, as another possibility, the aggregate produced in the recycling process of brick-containing masonry was supplied to concrete production as substitution material for the otherwise natural aggregate from gravel and sand (see details in »Table 2).

In »Table 3, for every variation, the percentage change of the specific environmental indicator is shown in comparison with the reference scenario (100 % cement clinker). The intensity of the colouring of the field indicates the strength of the increase or decrease of the environmental indicator compared to the reference.

5.1 Presentation and discussion of the results of the scenario

In the following, the results of the life cycle assessments (cf. »Table 3) of selected environmental impact categories are discussed individually.

For the greenhouse gas emissions and energy requirement, the discussion is conducted based on the individual departments. These are the composite material production, logistics, cement and concrete production. The exception is the comparison process with 100 % cement clinker, in which there is no composite material production and no addition of secondary resources. The department of composite material production constitutes the process chain from the resource of brick-containing masonry up to and including the cone crushers (cf. »Fig. 2). In this department, besides the energy consumption of the machines, their lubrication and the production of the machines are included. The same applies for the two departments of cement and concrete production. In addition, for concrete production, the infrastructure for water extraction and distribution are integrated. In the logistics department, the production, the deployment of vehicles and the use of the road infrastructure are taken into account.

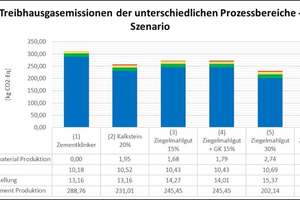

With the presentation in departments, the greenhouse gas emissions and energy requirement are partitioned and assigned to the causation process. »Fig. 3 shows the greenhouse gas emissions of the reference scenario (1) and the variation scenarios (2) to (6) in the different departments. It can be seen that cement production (100 % cement clinker) is the most emission-intensive process. For the greenhouse gas emissions, the reference process lies clearly above the other processes. A small difference in the greenhouse gas emissions can be seen in the comparison of the processes (3) and (4) as well as (5) and (6). Concrete production and logistics each cause around 5 % of the emissions of the cement production. For concrete production, the difference between the variants is the result of higher contents of fluxes and water for relatively high composite contents in the cement as well as the use of recycled aggregates as secondary raw material instead of sand and gravel as primary resources.

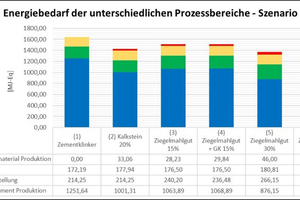

A similar result is obtained for the energy requirement, as shown in »Fig. 4. Cement production is the most energy-intensive process, although the differences are no longer as big as for the greenhouse gas emissions. The energy requirement for cement production is around a factor 4 to 5 higher than for logistics and concrete production. Cement production on the basis of clinker processing and the energy- as well as emission-intensive firing process in the rotary kiln has a considerably larger environmental impact than in the assessed alternatives.

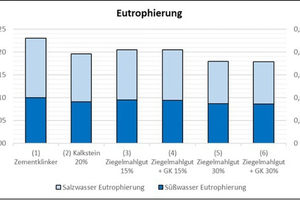

For the environment indicator eutrophication, changes in the excessive in-flow of plant nutrients in the form of inorganic phosphorous and nitrogen compounds in bodies of water are shown. With an increased introduction of nutrients, there results increased plant growth and the displacement of plant species that require less nitrogen. The result is a reduction in biodiversity. The scenario in »Fig. 5 shows that in comparison of the variants, hardly any change is observed in consideration of the freshwater eutrophication, however, there is a slight reduction compared to the reference scenario. In contrast, a considerable reduction is apparent in the saltwater eutrophication.

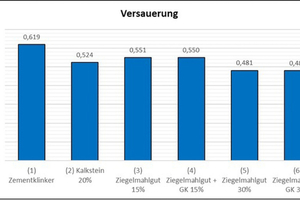

The environment indicator acidification refers to changes in the acid alkaline balance in bodies of water and soils. The release of acids leads to lowering of the pH value and poorer growth conditions for flora. In comparison with the reference scenario, the values with acidifying substances fall in the individual variations. Within the variations, there are, however, no big differences, as »Fig. 6 shows. Scenario (3) and (4) as well as Scenario (5) and (6) hardly differ.

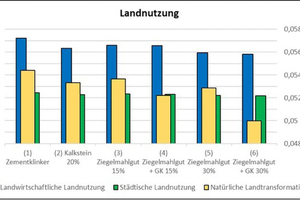

Positive changes are shown in the analysis of the environment impact of the environment indicator land use in the variations Scenario (1) to (6) (see »Fig. 7). The positive development can be attributed to the lower levels for the extraction of limestone in quarries and the reduction of the extraction sites for sand and gravel extraction for concrete production. In the short to mid-term, the extraction of natural resources leads to adverse effects. With early engagement with environment protection regulations and laws before and during extraction, intervention in the natural environment can be minimized. In the long-term context, with a renaturation at the extraction sites, new biotopes and expanses of water can be formed.

6. Conclusions and outlook

The key environmental impacts are generated during the production of cement clinker as result of the emission- and energy-intensive firing process. From this, it follows that the largest reduction of the environment impacts and the energy consumption is achieved by maximizing the cement clinker substitution rate. Ultimately, the possible substituted amount is the crucial parameter for the variation and lowering of the environment impacts. The optimum scenario would be the direct and complete integration of the recycled brick fines in the concrete production to ensure low environment impacts as well as a low energy requirement, but that is not feasible in practice.

The use of the recycled aggregate from the recycling process generates higher emissions, i.e. a 100-% substitution of natural aggregate from gravel plants with recycled aggregate leads to higher emissions. Nevertheless, it enables closure of material cycles with the utilization of secondary waste-derived resources as well as the protection of natural resources.

In the scenario, once the brick fines has been integrated primarily in cement production, other buyers, e.g. SMEs, private individuals, can also be considered. The use of brick fines is in any case beneficial also in respect of possible supply bottlenecks while the energy transition is still being set up. The use of fly ash and foundry sand as the currently used additive materials will end with the phasing out of coal-fired power generation by 2038 at the latest and the changeover of the pig iron production processes. Imports from abroad would be possible, but these are associated with higher emissions, and they are not always cost-efficient on account of the long-distance transport route. In the long term, brick fines could fill this gap as this is directly available without any long transport routes.

In the overall assessment, it is clear that the mitigation of the environmental impacts with the addition of limestone is greater than with the addition of brick fines (limestone: 20 %, brick fines 15 %). The addition of 30 % brick fines leads to a greater reduction of the environmental impacts than an addition of 20 % limestone.